Restrictions on the right to vote for convicted felons in the U.S.

By: Hannah M. Behncke, Mathea Kristoffersen, Camila Salazar Larsen, Selma Zachariassen Nasby, Eylül Sahin, Sabrina Eriksen Zapata - ELSA Bergen, Human Rights Researchgruppen.

This article was written and finished on November 5th, right before the beginning of the presidential elections. It is an expression of the authors' views.

This fall, the presidential election in the United States of America has gotten a lot of attention. This topic is relevant not only through its political aspect, but also the legal one and its implications on democracy. In this article, an overview over how a felony conviction can affect Americans voting rights will be presented.

An overview of the U.S.

Disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification, refers to the restriction of a person's right to vote. [1]

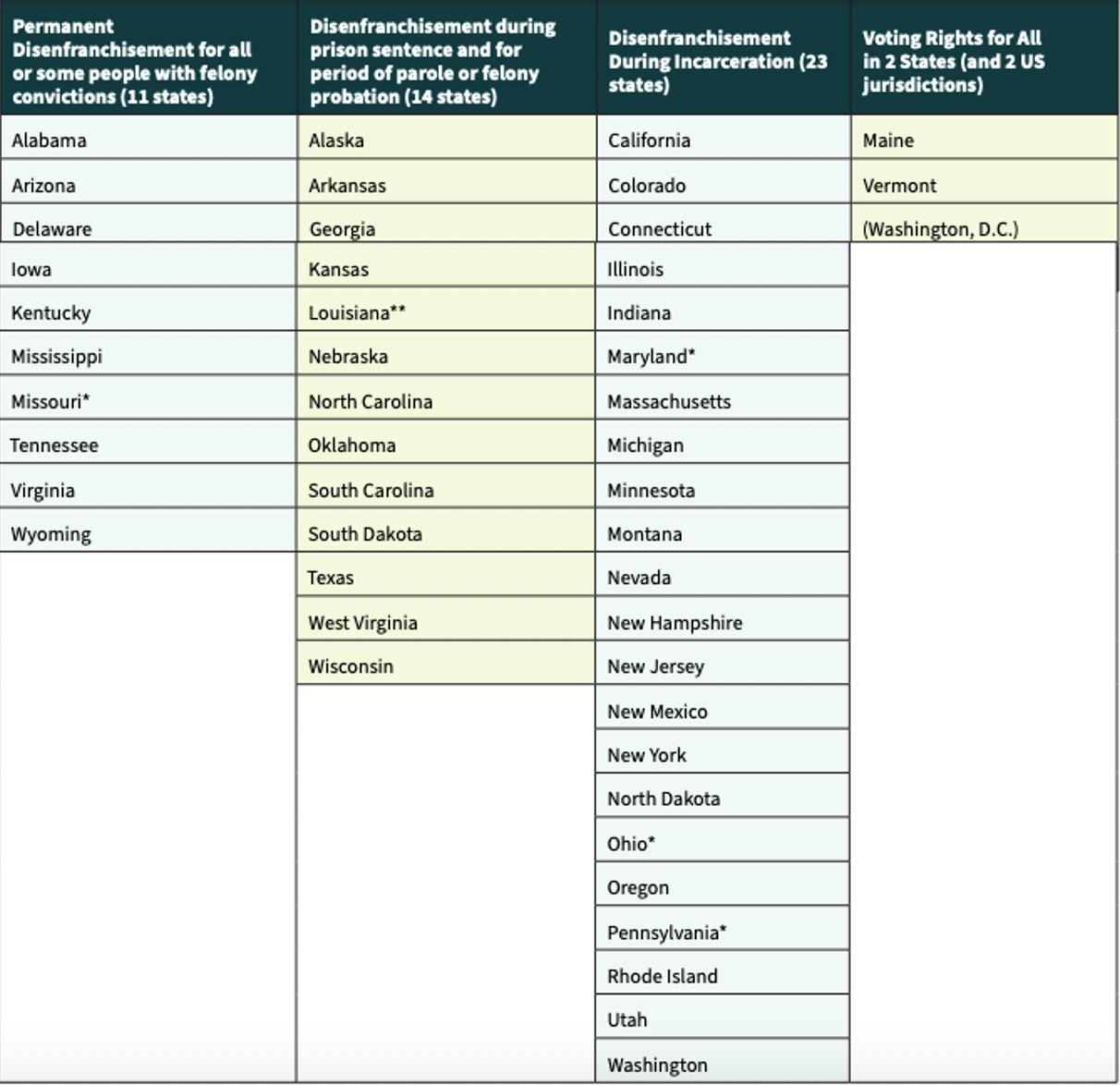

The United States has a federal system in which the states have two political authorities to adhere to, the national and subnational. It is the subnational level which regulates the right to vote for convicted felons. In some cases, felon disenfranchisement is permanent, whilst in other cases voting rights are restored after a former felon has completed probation, parole or served a sentence.

The legitimacy behind restricting convicted felons' right to vote comes from the Richardson v. Ramirez 1974 case. In 1972 Aban Ramirez sued the state of California, and challenged the state’s laws that permanently removed a convicted felons right to vote. The California Supreme Court agreed that this law was unconstitutional, however on appeal to the Supreme Court of the United State the decision was overturned. This meant that convicted felons could be prohibited from voting after completing their sentence and parole, without violating the “Equal Protection Clause” of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. This specific case has been used in the US as a means of legitimizing disenfranchisement. [2]

American policies regarding felony disenfranchisement have historically been so restrictive that the United Nations Human Rights Commission in 2006 condemned the US for violating international law regarding universal suffrage. [3] Whilst there has been a growing trend of restoring voting rights for convicted felons, the table below displays the limitations still imposed on convicted felons in the different American states. [4]

Problematics of Disenfranchisement

Around the world, there are many legal instruments establishing that punitive measures should go hand in hand with rehabilitation measures, so that individuals with a felony record can integrate back into society once their sentence is done. In particular, for our case of analysis, The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in article 10 (3) states that rehabilitation is one of the main objectives of a prison sentence. Although the U.S. ratified the aforementioned instrument in 1992, it did so with reservations to avoid conflict with national law. As mentioned before, historically, the U.S. has had a more punitive approach in their prison system, [5] but new laws that seek to change this scenario have been recently put into force at a national and federal level. For example The Second Chance Act (2008), The Fair Sentencing Act (2010), and The First Step Act (2018), seek the adequate reinsertion of convicts providing programs related to education, employment, and treatment of addictions.

However, an essential component of reinsertion into society requires participation in civic spaces, which includes the possibility to vote and choose your representatives. According to the United Nations, a “ civic space is the environment that enables people and groups (...) to participate meaningfully in the political, economic, social and cultural life in their societies (...) Any restrictions on such a space must comply with international human rights law. ” . [6] It seems rather contradictory that once an individual has complied with a felony sentence, and should then be ready to reintegrate into society, the person is still unable to participate in one of the most important processes one can find in a democracy. The aforementioned perpetuates exclusion and social discrimination, that ends up in a second-class citizenship. [7]

Furthermore, the voting bans on convicted felons are disproportionately placed on minorities, and especially on African Americans. There are 2% of adults in America at-large who cannot vote due to these bans, but this percentage is at 5% for African Americans, and at 1,5% for other groups of the population. [8] This shows that African Americans have a smaller opportunity than other groups in American society to elect people that best represent their interest, and more importantly, they have less of a chance to take part in their own democracy.

According to "The Sentencing Project", 4 million Americans do not have the right to vote in the 2024 election. [9] Although this number has declined by 31% since 2016, it is still a big issue, for example in elections with narrow winner margins. In the 2000 Presidential Election, the margin between Al Gore and George W. Bush in the popular vote was 540,000, which clearly demonstrates that a disenfranchisement population of 4 million might be enough to tip the scales between two candidates. At the state level, this margin is even smaller. In the 2020 Presidential Election, Joe Biden won the state of Georgia with a majority of only approximately 12 000 votes. [10] Georgia does not allow convicted felons to vote during their prison time, their parole or during probation. This leads to a total of almost 250 000 people being disenfranchised in Georgia today, a percentage of 3,25 %. [11] Consequently, the rate of disenfranchisement weakens democracy.

Moreover, it must be stated that felon disenfranchisement only restricts the right to vote, but convicted felons are still expected to participate in education or employment and pay the corresponding taxes, as any citizen is obliged to. As has been established by experts, taxation without representation contradicts the founding principles of the United States since the American Revolution, making the denial of governmental access while imposing taxes an urgent need of correction. [12] This prohibition causes a lack of fairness and accountability because taxpayers do not have a say on how the money will be spent, making individuals subject to policies and budgets they might not agree with.

Issues that arise even if there was a right to vote

Other than the problems connected to the legal eligibility to vote, there are remaining practical obstacles hindering the voting access for convicted felons. The first big obstacle is general voter confusion. The laws regulating voting access differ from each state and are frequently being changed. In addition, there have been several instances where governors have been issuing conflicting executive orders, and then rolling them back. A U.S commission on Civil rights also showed that correction officers frequently don’t provide information to returning citizens about their voting rights. [13] Seen in light of the fact that many states prosecute people trying to vote when they don’t realize they aren’t eligible to do so, the risk could be seen as too high for a lot of voters.

Another obstacle for voting is that many states require various forms of documentation in order to vote. Other than the fact that getting the documentation in itself could be a long process, the conditions for getting the paperwork could be problematic. As an example, getting the voter rights certificate in Louisiana demands that the applicant has not been incarcerated for the last five years. [14] In many states the returning citizen only has a right to vote after paying a list of legal financial obligations. It’s not to be argued that people returning to society after long convictions often don’t have a stable economy. As an example of this issue, about one third of applications for rights restorations in Alabama are denied due to debts to the courts. [15] Lastly, some other obstacles could be directly connected to the serving of jailtime itself. Logistical hurdles, lack of voting opportunities, learning and meeting the deadlines for voting, getting an ID etc. could represent further hurdles.

A european perspective

The deprivation of voting rights should be exceptional, determined by a judge on a case-by-case basis with a clear link between the offence and democratic institutions to ensure proportionality. [22] However, it is important to note that the absence of judicial oversight does not necessarily imply a blanket restriction, as a well-defined legal framework may suffice. [23]

Prisoners' voting rights in Europe remain vulnerable, as evidenced by the 2022 judgement in Kalda v. Estonia (No. 2), which upheld a general ban on voting for prisoners. The Court ruled that national courts had appropriately assessed the measure's proportionality on a case-by-case basis. This ruling facilitates increased restrictions, enabling states to justify general bans based on assessments of inmates’ dangerousness.

The emphasis on prison security and negative public attitudes undermine prisoners' voting rights, which the Court highlighted as vital for resocialization and reintegration in Viola v. Italy (No. 2).

Challenges such as access to information, political propaganda, and voting organizations hinder the effective exercise of this right. [24]

Final remarks

The exclusion of felons from voting in the U.S. raises issues related to justice, representation, democracy and reintegration. Although recent developments support restoring voting rights, significant practical and legal barriers still exist. Comparisons with international norms suggest that U.S. policies are unusually restrictive.

[1] Retrieved 05.11.2024 from

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/disenfranchisement#google_vignette

[2] Staufenbeil, Kiley (2020) "With Liberty and Justice for Some: How Felony Disenfranchisement Undermines American Democracy," Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science: Vol. 8 , Article 6. https://doi.org/10.31979/THEMIS.2020.0806 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/themis/vol8/iss1/6

[3] ACLU, 2006, https://www.aclu.org/documents/un-committee-says-us-bans-former-prisoner-voting-violate-international-law

[4] Human Rights Watch, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/media_2024/06/Out%20of%20Step.pdf

[5] Chapter 5 The Sprawling Punitive Turn, 1993–2001 Michael S. Sherry

https://doi.org/10.5149/northcarolina/9781469660707.003.0006 Pages 131–172 Published: December 2020

[6] European Union. (2024). European Union Agency for Fundamental Right. Civil society and the Fundamental Rights Platform. https://fra.europa.eu/sq/cooperation/civil-society/civil-society-space

[7] Taxation without representation. (n.d.). https://static.prisonpolicy.org/scans/ririghttovote/RTVWhitePaper.pdf

[8] Christopher Uggen, Ryan Larson, Sarah Shannon, and Robert Stewart, “Locked Out 2022: Estimates of People Denied Voting Rights,” sentencingproject.org

[9] The Sentencing Project, october 2024: https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/locked-out-2024-four-million-denied-voting-rights-due-to-a-felony-conviction/

[10] CNN, https://edition.cnn.com/election/2020/results/state/georgia

[11] The Sentencing Project, 2024

[12] Taxation without representation. (n.d.). https://static.prisonpolicy.org/scans/ririghttovote/RTVWhitePaper.pdf

[13] Un commission on civil rights, June 2019, Collateral Consequences: The Crossroads of Punishment, Redemption, and the Effects on Communities . Retrieved november 4th 2024.

[14] Human rights watch (2024). Out of step, US policy on voting rights in a global perspective. Human rights watch. Retrieved 04.11.2024 from

https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/06/27/out-step/us-policy-voting-rights-global-perspective

[15] U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, pg. at pg. 118.

[16] ECHR, Thematic Note – Voting Rights of Inmates. December 2022.

[17] ECtHR, Campbell and Fell v. United Kingdom, no. 7819/77, para. 69.

[18] ECtHR, no° 17504/18, para. 43 and 52

[19] ECtHR, Kalda v. Estonia (n°2), n°14581/20, para. 39.

[20] CtHR, Scoppola v. Italy (n°3), n°126/05.

[21] Dalloz Report, 2013, p. 2174, Prisoners' Right to Vote: Conviction of Turkey, Judgment by the European Court of Human Rights, No. 29411/07.

[22] ECtHR, Frodl v. Austria, n°20201, and Cases like Hirst v. United Kingdom and Scoppola v. Italy have highlighted the limits of state discretion in this area.

[23] Olivier Bachelet, “Voting Rights of Prisoners: The Strasbourg Compromise”, Comment on ECHR, Grand Chamber, 22 May 2012, Scoppola v. Italy (No. 3) , No. 126/05 in Dalloz News, 15 june 2012

[24] Élise Boulineau, “Convicted people’s right: a matured right?”, RFDA 2024, p. 125.